Optimisation time, huh? Welcome to the big leagues!

If you’re at this stage you should definitely have your financial house in order - ‘optimising’ a bad foundation is a complete waste of time!

What does ‘financial house in order’ mean?

- You have ZERO bad debts (see Chapters 2 & 3)

- You are maximising your savings (see Chapters 6, 7 & 8)

- You are maximising your earnings (see Chapter 9)

- You have an emergency fund in place (see Chapter 10)

- You are consistently investing (see Chapters 11, 12a, 12b & 13)

If you don’t look at that list and think to yourself ’yes, yes, and yes’, then stop reading now and go straight to the chapter that you’re not sure about and make sure you’ve got it covered.

Honestly, if you’ve ticked off everything up to this point, you should already achieve FIRE. This section’s aim is just to help you get there a bit faster. But if you don’t have everything up to this point covered, then you can read this section and you may still never reach it!

So, first things first - get your financial house in order!

Next point is that I can’t say, hand-on-my heart, that researching & implementing the concepts contained in this section are actually the best way to spend your time.

One of my favourite arguments against picking stocks is “look, even if you could pick stocks in your free time better than the guy at Goldman Sachs who gets paid to do it for a living, is that really going to give you the best return on your time?”

My key point here is that when we’re dealing with relatively small amounts of money, like anything less than millions, the time spent getting an extra 1% return on your funds would usually been better spent working more in your main job, or on the side - not to mention that an additional 1% return above vanilla ETFs for the same level of risk is extremely hard to do!

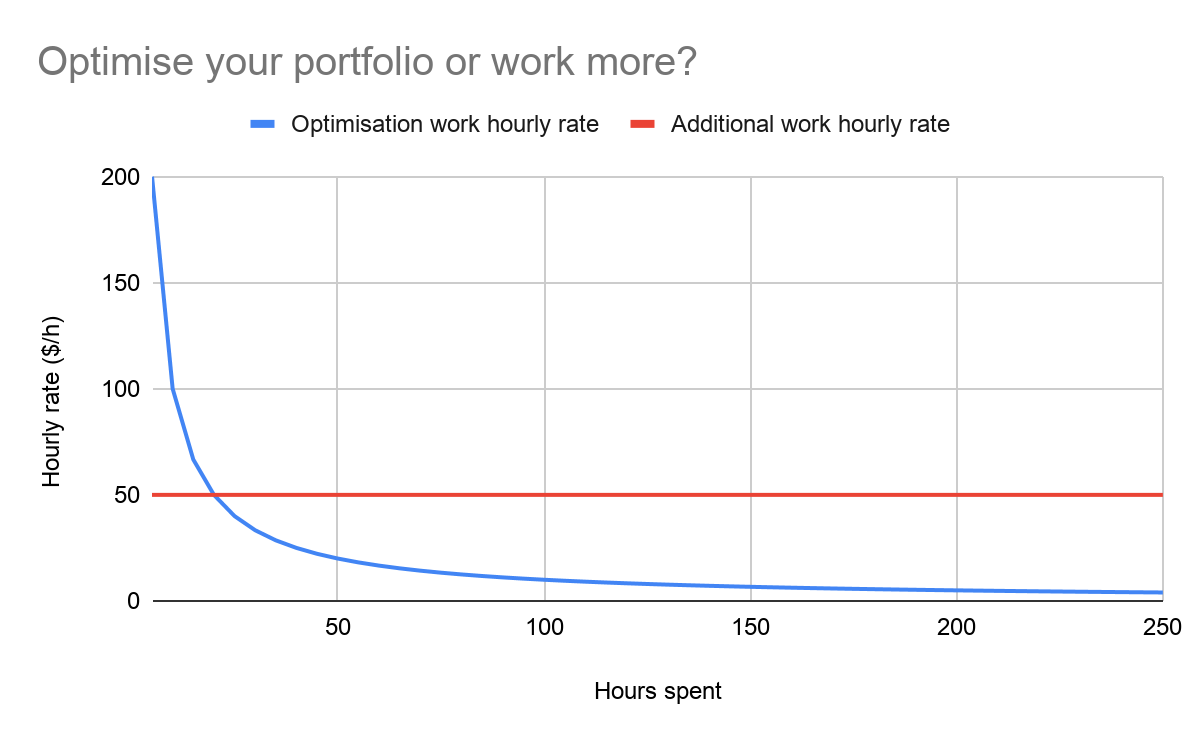

For example, let’s say you have a $100,000 portfolio and have the talent to earn 1% more than regular ETFs. How many hours would it take you to get that extra 1%? And would those hours spent be worth it?

Well, let’s assume that any time you spend optimising your portfolio could be just as easily spent working additional hours somewhere & being paid $50/h. Here’s how the numbers look…

In this case, if you have to spend more than 20 hours getting that extra 1%, then it’s not worth it.

If you like, you can calculate the trade-off for your own circumstances.

So, now you’re aware of the trade-off you’re making from a purely financial point-of-view and you’re going into this optimisation stuff with eyes wide-open.

Maybe it doesn’t make sense for you to invest the time optimising, but you’re a personal finance nerd like me and enjoy working through this stuff - if so, welcome! You’ve just found nirvana! 😂

Or maybe you are a high-roller (#FATFIRE) and it makes complete sense for you to invest the time optimising your portfolio?

Either way, this chapter, and this whole section, is written for you.

Ok, so when it comes to portfolio optimisation, the place we need to start is with Modern Portfolio Theory, or MPT, because this is the foundation you need to understand the risk/return consequences of your portfolio tweaks, which when it comes to investing, is all that really matters.

I will say though that getting into the nitty-gritty of risk/return optimisation isn’t light-reading, so be warned! We'll be covering important information you need to optimise your portfolio. Specifically:

- An introduction to Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT)

- Put the theory to practice

- Using leverage

- The outcome

Alright, time to get started, we're not getting any younger.

An introduction to Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT)

MPT is a Nobel Prize-winning investment theory pioneered by a bloke called Harry Markowitz in 1952 that today forms the basis of how most professional investors put together their portfolios, including hedge funds, managed funds and super funds.

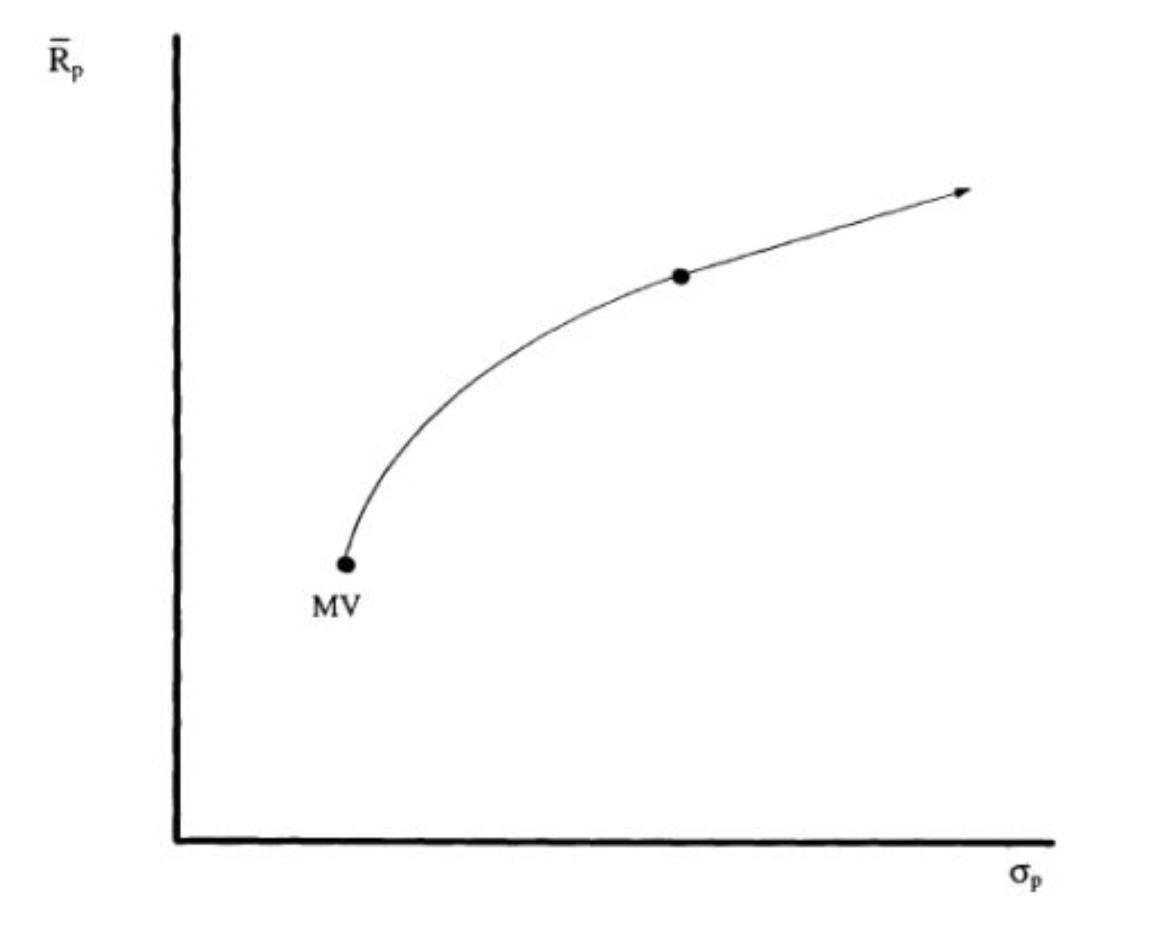

It states that since most investors are risk-averse (i.e. don't want to lose money), they require more return for taking on more risk, that for each level of risk there is a corresponding combination of assets that maximises return, and that of all these portfolios, there is one that maximises the risk-return trade-off - this is known as the Optimal Portfolio.

Note that the risk accounted for in this trade-off is "systematic risk," which means the risk factors that are present affect the whole market and cannot be eliminated through further diversification. This type of risk is measured as standard deviation and therefore is a measure of how extreme market movements are, not necessarily the risk of losing your capital. We'll get into the difference in more detail later.

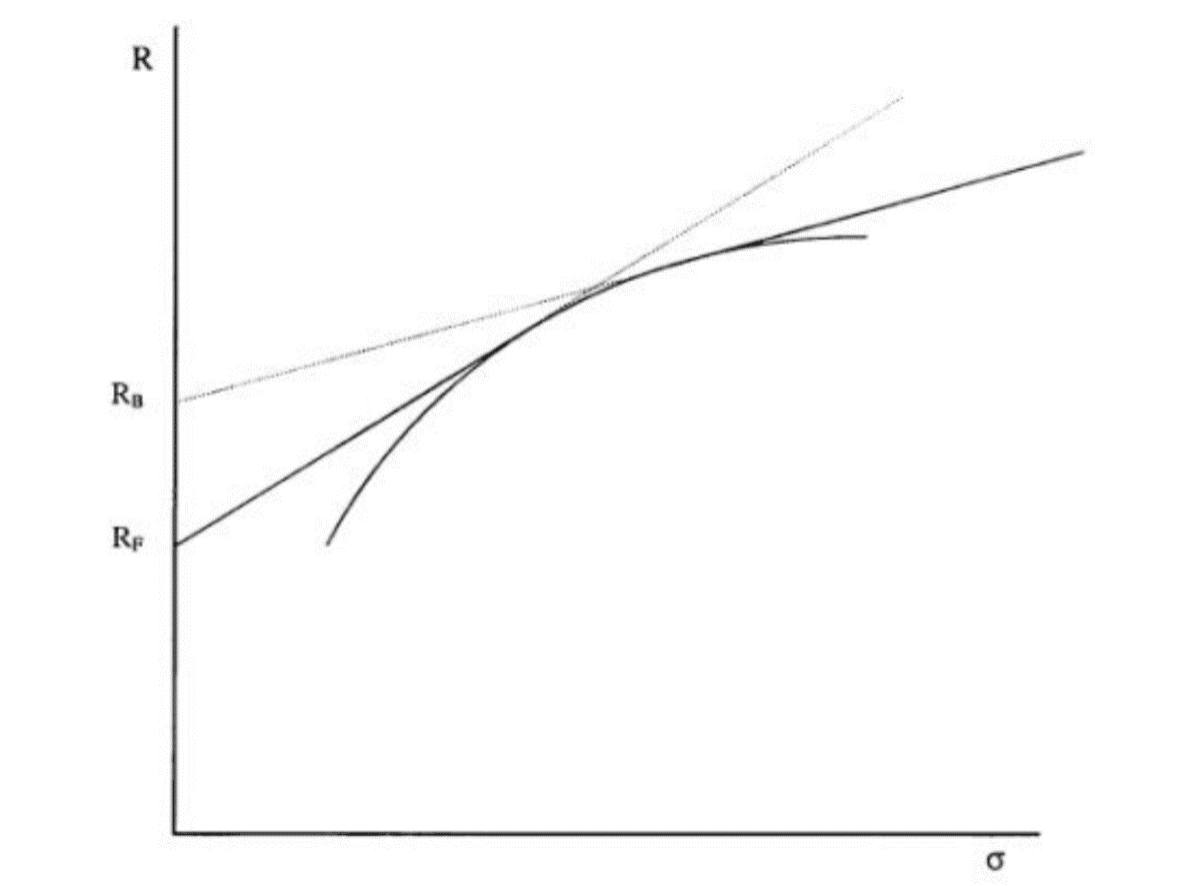

Ok, so here's what the range of portfolios (known as the efficient frontier) looks like. The right axis is return (% pa) and the horizontal is standard deviation. The line is the efficient frontier. MV stands for mean variance. The efficient frontier is comprised solely of non-cash assets.

So, where on the efficient frontier is this optimal combination of assets?

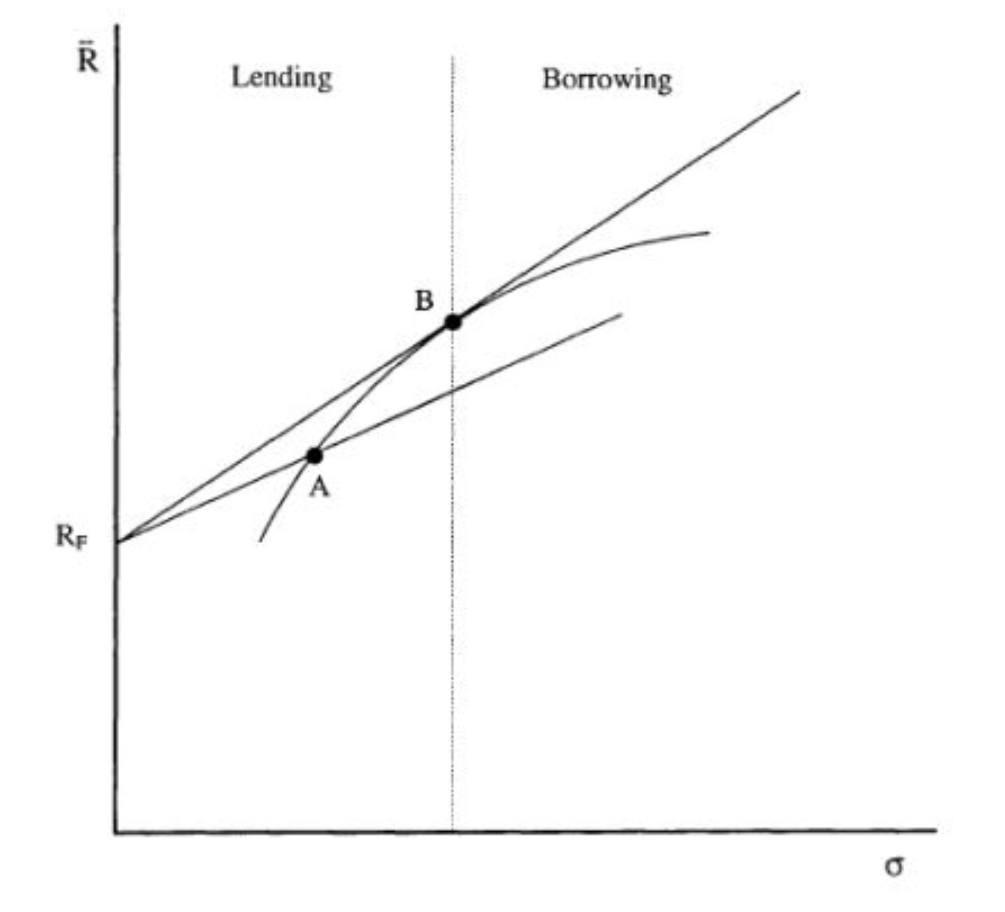

To figure that out we first need to introduce the concept of the risk-free rate, or Rf, which is the rate that investors can borrow or lend money at. Theoretically, Rf allows us to lend money by buying risk-free assets with extra cash, or borrow money by loaning some extra cash to invest in the optimal portfolio.

Then, if we draw a line between Rf and the efficient frontier, the point on the efficient frontier that maximises the slope is the optimal portfolio (i.e. point B = Optimal Portfolio in the graph below).

Note that the gradient of the line between Rf and B is the Sharpe ratio and the line itself if called the Capital Market Line. This means that the portfolio of assets at point B maximises the Sharpe ratio and the best return achievable in the Market for any level of risk is plotted along the Capital Market Line.

So, how do we move along the Capital Market Line? Well, any of these points can be achieved by allocating a proportion of funds to the optimal portfolio and the rest to cash. We can even allocate a negative proportion to cash, i.e. we move along the line by lending or borrowing at Rf.

Theoretically, investors move along the line to their own "happy risk point" by lending or borrowing at the risk free rate to maximise the return they get for the amount of risk they're willing to bear.

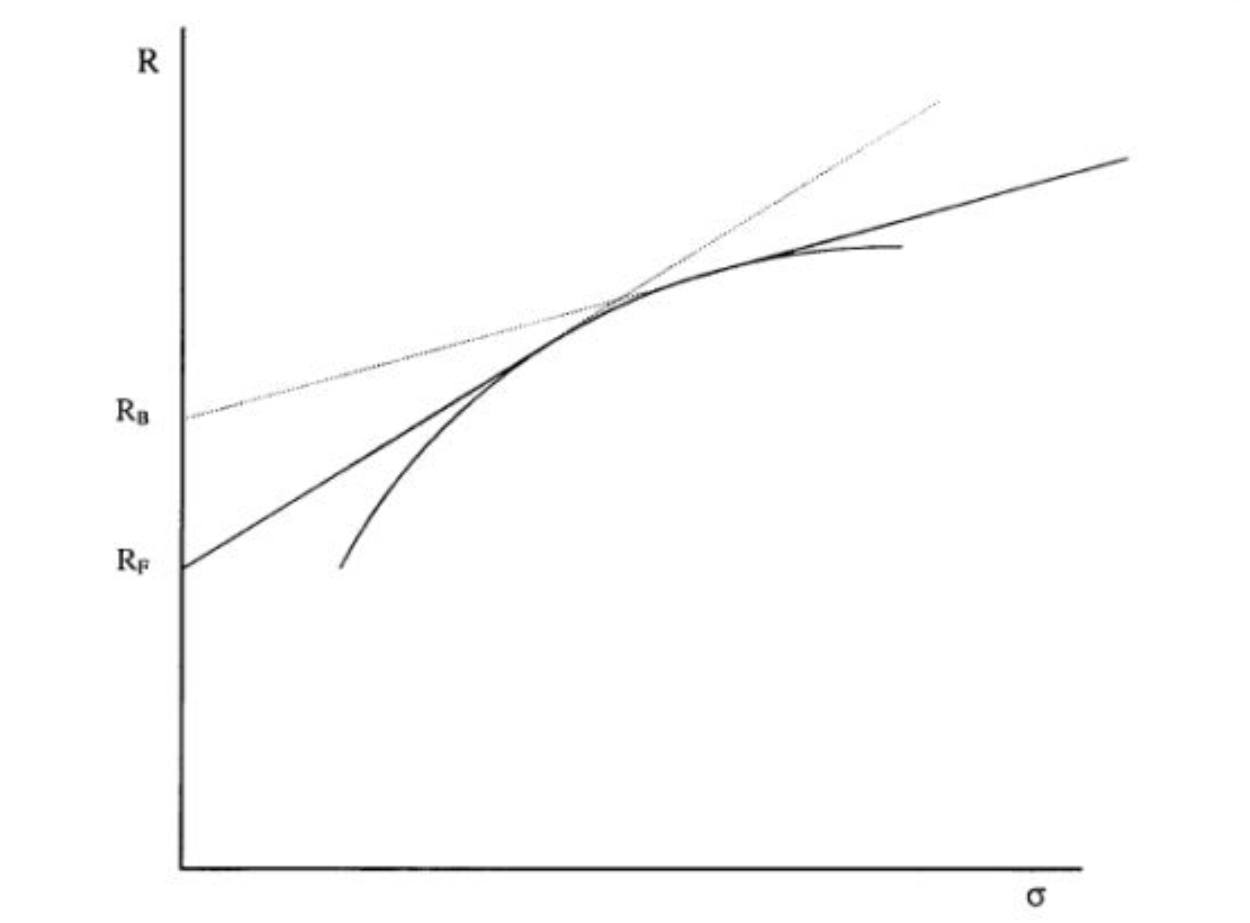

Problem is, in practice, investors cannot borrow at the same rates they can lend. Investors can lend close to 'risk-free' by buying government bonds, however, we will always pay a higher borrowing rate than what we can lend at.

So, if our lending rate is different to our borrowing rate, then the capital market line becomes kinked, as shown below.

In this case, instead of having one optimal portfolio, there is a range of optimal portfolios between the two points of intersection of Rf and Rb. The higher the difference between Rf and Rb, the greater the number of optimal portfolios and the more the benefit of leverage is reduced.

Using current figures, AU Government bonds yields are around 1% p.a., but most margin loans will cost you closer to 5% pa. So yes, it seems like an unfair trade, plus there's a bit of work involved in setting up margin accounts and monitoring asset values.

This is why I'd dismissed leveraged investing as a viable option for my own portfolio for a long time.

Put theory into practice

As you’ve just read, MPT is built around the concept of an optimal or market portfolio.

In theory, this optimal market portfolio is a bundle of investments that includes every type of asset available in the world financial market, with each asset weighted in proportion to its total presence in the market (yes, the name kind of gives it away)! But how do we invest in every asset in the world in the right proportions?

Simply put, we can't. We're retail investors with limited time on our hands. But, by using ETFs we can get close enough with not much effort.

First, we need to decide on how much risk we're comfortable with. As mentioned before, I don't think of this risk as risking capital loss because it's not. Standard deviation is a function of volatility, not permanent loss and therefore the true risk is being unable to withstand temporary value decline, psychologically or financially.

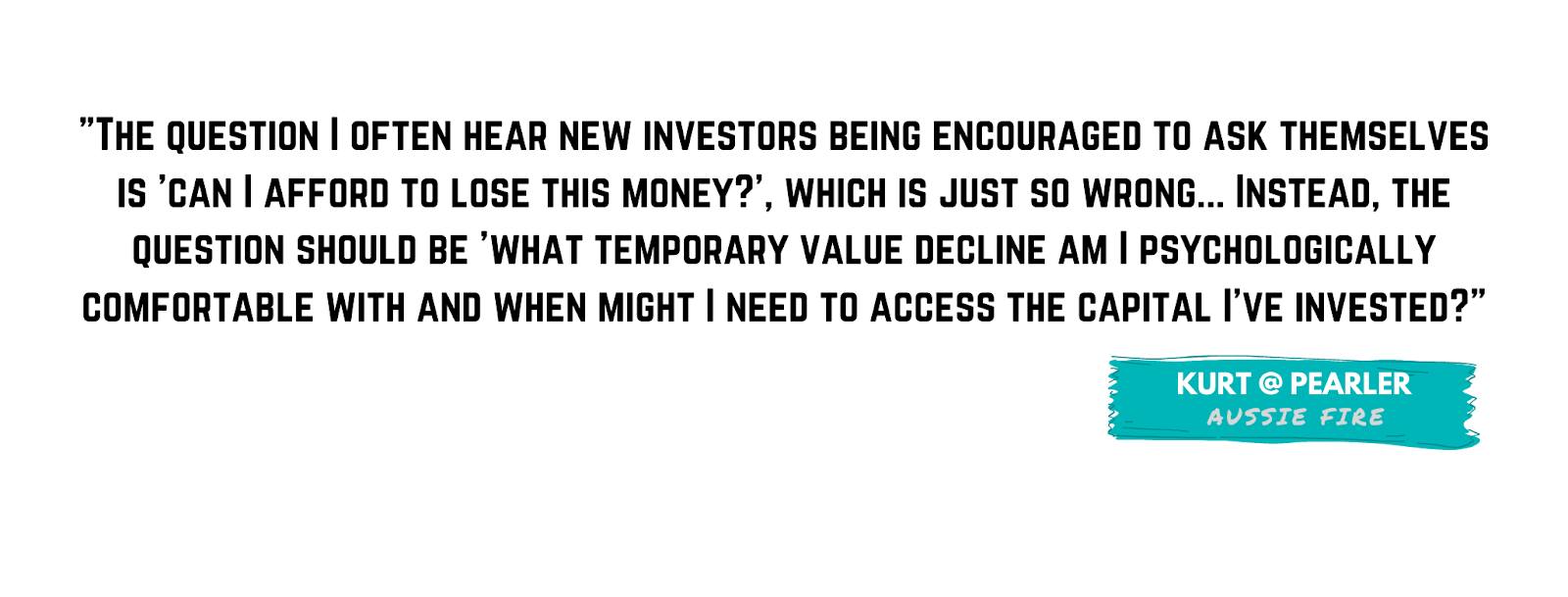

This is a subtle difference but an important one. The question I often hear new investors being encouraged to ask themselves is 'can I afford to lose this money?', which is just so wrong.

Thinking this way further reinforces the misconception that investing is gambling - the same misconception that stops so many Aussies from becoming investors in the first place.

Instead, the question should be 'what temporary value decline am I psychologically comfortable with and when might I need to access the capital I've invested?'*

So, there are two parts to this question. Firstly, how can we measure our psychological ability to withstand temporary value decline? And secondly, what are our future needs for our invested capital?

I think we can use past experience as a conservative way to estimate our psychological tolerance to temporary value decline - e.g. think about what's been the worst decline you've been able to ride-out and go from there.

For me, this was the GFC. I made my first investments in 2007 and come 2008 my investments were worth 75% less (perfect timing!). I didn't sell any shares until 5 years afterwards so I expect I can ride out another 75% value decline, if it were to happen (which is extremely unlikely as I now mostly invest in ETFs).

With COVID rocking the markets recently, you should have a pretty good idea of how much volatility you can psychologically withstand - were you stressed? Did you sell? Or didn’t you even break a sweat?

But what if you haven't had to deal with a market crash yet? Or you think my past-experience approach sucks? Well, you're in luck. There are a bunch of Risk Profiling quizzes you can take, like this FinaMetrica one. If you’ve got a .edu email it’s free. The front page of my report is below. My results were what I expected. I imagine most FI-investors would be towards the upper end of this range.

Together, these two methods should give you a solid understanding of your investing psychology.

Next, we've got to consider our future needs for invested capital, both planned and unplanned. This is hyper-personal and I don't know of a broad way to give guidance here, but here are my circumstances:

- I don't intend to access my current investment capital ever. This capital and a portion of my future capital is being used to become FI (financially independent), my #1 financial goal.

- I haven't set other personal financial goals yet and apart from a lumpy income, my financial affairs and commitments are uncomplicated - not married, no dependents, etc.

- When new goals do arise, I expect to be able to save for them in a way that doesn't compromise my FI-investing strategy.

- In particular, when my life circumstances change and I want to purchase a house and other big-ticket items, I don't think my need for capital to purchase these items will ever be so urgent as to force me to sell at bad prices, if I need to sell at all.

- I have private health insurance and always cover myself with travel insurance when abroad.

- If everything goes wrong I have a family safety-net to fall back on.

The outcome of my personal circumstances is pretty simple. I intend to never need my invested capital that I put towards FI for anything other than achieving FI, and I am confident my circumstances will allow me to do this for 20 years.

But what if it wasn't so straightforward? Let's say that I plan on using this capital for a home deposit in 5 years time. How should I change my strategy?

Well, for me it would depend on how fixed I am on that 5-year timeline. If I would like to own a home, but not have to, then my strategy would remain very similar - I would just invest in the way that maximises my return over the long-term. If the sharemarket plugs along normally I'll be fine, and if it shits itself I will just wait until it rebounds.

Of course, this all changes if I must buy a home in 5 years. In this case, and with a 5-year timeline, my capital really isn't safe in the market. Historical figures suggest I could lose up to 12% of capital invested over rolling 5-year periods, and 37% over rolling 1-year periods. So the decision now becomes a toss-up between how much I am willing to risk having to purchase a less expensive property vs the additional expected return.

The difference is ~2% per annum in a HISA vs ~10% per annum in the market, or about 5x!

Note that this isn't a static decision either, because as the timeline becomes shorter my risk of capital loss increases. It's a tough call that will be unique for everyone - far simpler to avoid getting into the position where I must do anything with my capital, I reckon.

So, taking stock of my situation: I've got no fixed future obligation for invested capital and I've withstood a ~75% temporary value decline before. This means I can withstand a lot of volatility and so I am a fair way to the right on the horizontal axis below.

As you can see, I'm past 'the kink' and so should theoretically have a leveraged portfolio with a mix of bonds and equities.

Up until recently though, I wasn't aware of any viable ways for retail investors to invest with leverage.

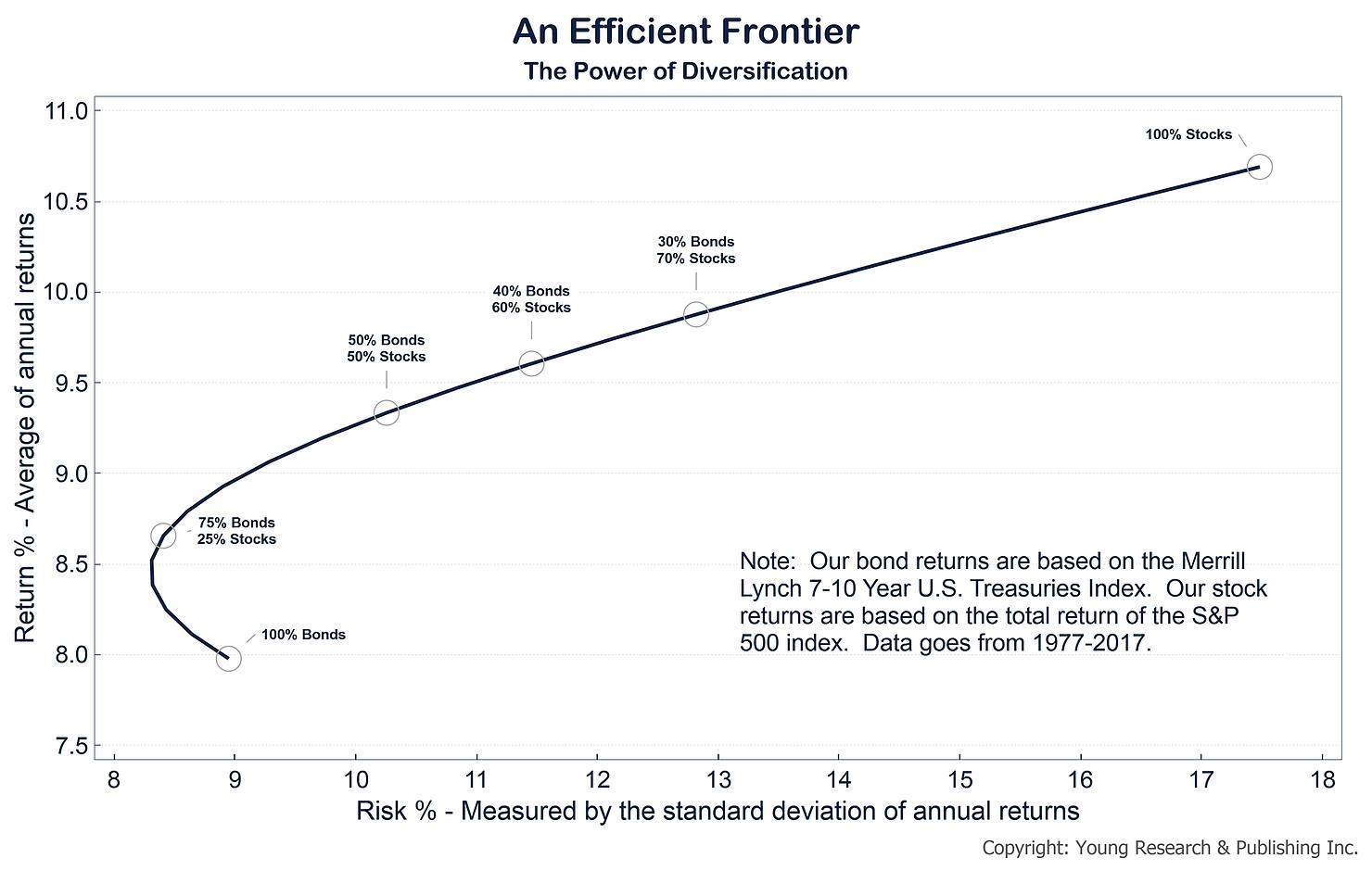

The costs of margin loans (~5% pa + active monitoring) just didn't make sense, so my strategy to cost-effectively maximise my return had been to invest all my cash in AU & global equity ETFs and forgo bonds completely, as per the efficient frontier asset allocations below. **

As you can see, a 100% equity portfolio is theoretically how to maximise return if leverage is cost-ineffective.

Theoretically, MPT uses the market-weighted portfolio (an all-world, all-equity, market-weighted portfolio with assets allocated based on risk profile). If there were no tax or currency considerations to take into account, this would mean we should allocate less than 5% of our funds to Aussie investments!

In practice though, there are regulatory benefits for Australians to invest in Australia (franking credits, dividends & currency), which are the main reasons that the ideal all-equity portfolio for an Australian has a much higher concentration of Aussie equities than 'market weight'.

As you can tell, I’m a bit of a nerd about this stuff and I researched the theoretical optimal domestic asset allocation for Australians quite heavily.

While I didn’t find exactly what I was looking for, I did find a journal paper from 2013 that looked specifically at Aussie equities! Here’s the key takeaway:

Overall, the optimal allocation to equities from the perspective of a taxable Australian investor is between 32% and 60%, with higher allocations leading to lower volatility of the overall equity portfolio.

So, extrapolating this to other asset classes (which seems valid, but I may be wrong), typically we’re looking at the 30% to 60% Aussie asset allocation range. Note that this study assumed the top tax bracket, pushing the optimal allocation higher than it would be for investors in lower tax brackets. Still, I think that it’s fair to assume that for all tax brackets, this range is accurate enough to use.

Using leverage

I’d assumed for years that leverage was just too cost- and time-ineffective to use to invest in equities (for those of us on the far RHS of the Efficient Frontier).

5% p.a. margin loans to earn ~10% p.a. with 32.5c tax to pay on every additional dollar of income plus the stress of margin calls just doesn’t appeal to me.

Over the past few years though, I’ve discovered that there are ways to cost- and time-effectively invest in equities with leverage.

The most well-known and widely recommended is debt recycling. Debt recycling is a process that essentially allows you to invest in shares with leverage at the same interest rate as a home loan, while making the interest tax-deductible.

Debt recycling is the most widely recommended for a good reason; it mitigates the two biggest downsides of margin loans:

- Stressful margin calls

- Prohibitively high interest rates

But, there’s one key ingredient you need that many of us who are early on our FIRE journey don’t have - a house!

So, if you have a house and are interested in leverage, I strongly suggest you read this awesome guide to Debt Recycling by A Family on FIRE, and another Debt Recycling guide by Dave from Strong Money Australia too.

But, if you’re like me and don’t own a home, then what do you do?

One option I've been testing out over the past year is Internally Geared ETFs, which are effectively corporate margin loans for retail investors.

They are a relatively new product category and there are only two ASX-listed options - GEAR which tracks the ASX200 and GGUS which tracks the S&P500.

Currently, the borrowing rate for them both is ~2% and the leverage is centrally managed by the ETF provider, making them much more time- and cost-efficient than the traditional margin loan alternative.

But, we are in an extreme period of volatility, and internally geared ETFs underperform in extreme volatility because they have to rebalance often.

Still, they are the best-leveraged investment option I know for retail investors who don’t own a home in Australia, so if you’re interested in leverage and don’t own a home I recommend you read my detailed analysis of Internally Geared ETFs.

To be complete, another worthwhile consideration is NAB’s Equity Builder. This product essentially allows you to to take out loan to invest in a selection of ‘safer’ assets, including most Aussie ETFs.

It’s fees are stilll quite high (~4% p.a.), but it doesn’t have any margin calls. The repayment behaviour is like a blend of mortgage and margin loan and is generally pretty customer-friendly.

Similar to buying a house, the Equity Builder can incur a fair bit of pricing risk if not used intelligently though- you want to DCA and not lock in the price at a market peak (unfortunately you don’t have this option when buying a house!).

For more information, read this thorough review about NAB's Equity Builder.

The Outcome

Now you’ve got the foundation to start optimising your portfolio.

Work out what your risk tolerance is. Work out when you need access to the capital you’re investing. Then work out what that means for your asset allocation and apply it.

It’s as simple as that.

About Kurt Walkom | pearler.com

Kurt is one of Pearler's co-founders. After reading the Barefoot Investor at the ripe old age of 14, Kurt got started on his Financial Independence journey early. He invested his $15,000 in "life savings" in 3 stocks based on a stockbroker's recommendation – right before the Global Financial Crisis. Seeing his share portfolio plummet in value (and never bounce back), Kurt resolved to learn all he could about investing, and why retail investment advice gets it so wrong, so often. In 2018, Kurt co-founded Pearler with his two friends, Hayden and Nick, to make it easier for everyday Aussies to invest in shares the right way - incremental amounts in diversified portfolios, for the long-term.

*This is the part where the past performance is not an indicator of future performance BS disclaimer usually features, but I'm taking a stand because if your time horizon is long enough and you invest with adequate diversification, your chances of permanently losing your capital are zero, unless the world suffers a cataclysmic catastrophe (then we're all F###ed). What is an adequate diversification/time horizon mix? And what's a cataclysmic catastrophe? Well, if you invested in the top 500 companies listed in the US alone, there's not one rolling 20-year period since 1872 that would've lost capital value… Not one of the world wars, financial crises or natural disasters was enough of a catastrophe to stop the relentless progress of the sharemarket for 20 years.

** It's important to make sure that the dataset of the efficient frontier you're using is over a sufficiently long time frame. Crudely applying MPT with short-term data can have an over optimisation problem, i.e. it will just pick and promote recent 'hot' asset classes.

A big thanks to d42.com for providing most of the efficient frontier images used in this article.

NOTE: Aussie FIRE is a free educational resource prepared by Pearler, with permission from the co-authors. At Pearler, we strive to make investing for your long-term goals easier and fun, but we only provide general information and/or general advice. We don’t present you any options based on your personal objectives, circumstances, or financial needs. Any advice is of a general nature only. All investments carry risk. Before making any investment decision, please consider if it’s right for you and seek appropriate taxation and legal advice. Please view our Financial Services Guide before deciding to use or invest on Pearler.