Last week, global stockmarkets had their worst week since the GFC. Coronavirus, aka COVID-19, has everyone spooked – governments, financial markets, and the public. Now definitely feels like a bad time to be investing, but is it?

Amongst the hustle and bustle of everyday living, coronavirus appears to be a freak occurrence. It seems like markets are irreparably tanking, countries are irrevocably becoming more insular, and the official ‘pandemic’ classification is inevitable. 😱

Before we make any decisions though, especially financial ones, we need to take a step back and look at the bigger picture. We are talking about investing after all, which is all about the long-term. Successful investors don’t change their carefully considered +10-yr strategies based on short-term crises, however scary they may seem at the time.

So, taking that step back, the three factors we need to explore are:

- Is coronavirus a short- or long-term crisis?

- Can I reliably time the coronavirus correction?

- The key takeaway

Is coronavirus a short- or long-term crisis?

In the moment it can be hard to make decisions with a long-term outlook without being overwhelmed by emotions. Our best defense against them is to be ruthlessly analytical. And history can help us here. Instead of looking at what’s happening today, let’s look at similar events that have happened in the past and compare with the effects they had on financial markets.

In the case of SARS, Swine flu, Ebola, and Zika – the four most recent large epidemics – one month after each crisis peaked, the market completely regained what it had lost and then some. Check out the stats for yourself below.

This is classic short-term market behaviour – wild swings when uncertainty is introduced, then stabilisation and return to historical trend when uncertainty subsides. 3 months on from the peak of each of these outbreaks the respective markets (where each epidemic originated) had forgotten what all the fuss was about. No pervasive long-term economic damage is to be seen.

How does Coronavirus stack up? Well, since the start of the outbreak there has been a ~7% reduction in the Chinese market (MSCI China) and a ~9% reduction in the global market (MSCI World) to-date. Additionally, both markets have rallied recently (a ~5% gain since 1 Feb for China and ~2% gain since 27 Feb for World).

What does this mean? Well, considering the largest peak-to-trough changes are ~12% and ~11% for MSCI China and MSCI World respectively, coronavirus has already created larger market swings than SARS, Swine flu, Ebola, or Zika. But also, the recent rallies suggest that the market sentiment on coronavirus is following a similar trend. Is recovery imminent? Who knows…

But even if it was, what do we care? We’re long-term investors chasing Financial Independence - we shouldn’t give two shits about market sentiment and short-term swings! 💩💩

So, getting back to the main game - are pervasive long-term economic impacts likely and if so, would they change our investing strategy? Before answering this one let’s take an even larger step back – to 1970 – and look at how the world stock markets have coped with epidemics over the past 50 years.

Note: the MSCI World Index captures large and mid-cap representation across 23 Developed Markets countries. With 1,644 constituents, the index covers approximately 85% of the free float-adjusted market capitalization in each country.

As you can see, historcially, epidemics have done rather poorly at influencing the direction of the market in the medium- and long-term. There also seems to have been a relatively larger concentration of epidemics over the past 25 years than the 25 years before that – the result of better diagnosis tools perhaps? In any case, as a global society we haven’t been enormously economically impacted by epidemics before.

Is coronavirus different from the rest? Yes and no. As you can see on the chart below, coronavirus is a more potent infectious disease than the more recent novel outbreaks, and we don’t have a vaccine for it yet. BUT it’s not as potent as some older diseases such as Smallpox or Measles.

Notably, COVID-19 is both more deadly and more transmissible than the seasonal flu – by around 10 - 50 times. Therefore, if it becomes uncontainable (and according to some it already has), we should conservatively expect a 50x long-term economic impact.

Influenza’s annual cost is ~$8.5 billion, so a 50x cost equates to $425 billion per annum. This isn’t negligible, but it also isn’t world-ending. Last year, global real GDP growth was $2,516 billion, so in a worst-case scenario, global GDP growth may slow by 20% from purely illness-related costs.***

What this doesn’t take into account is the cost of shutting borders and disrupted supply chains. Globally, economies will continue to shrink in the short term as more ‘border blocking’ takes place in an effort to contain the virus.

And yes, this ~~may trigger~~ has triggered much a larger downturn. (updated May 2020).

How long will this all continue? Probably until it’s either contained, or declared uncontainable, and the general public realises closing borders is unnecessary.

The daily tally of new cases in China peaked and then plateaued between Jan. 23 and Feb. 2, and has steadily declined since. If governments around the world follow suit with similar aggressive responses, it may yet be able to be contained.

But if not, total economic costs due to illness are proportionate and vaccine should not be more than two years away.

So for you as a long-term investor, if you’re invested in blue-chip companies with solid balance sheets and risk mitigation strategies, or better yet broad-based exchange-traded funds (ETFs), coronavirus shouldn’t give you nightmares. Stop watching your portfolio, turn off the news, and stick to your tried and tested strategy.

In fact, if you want to do anything, your first consideration should be to buy more while they’re on sale!

This brings us nicely to the next section…

Can I reliably time the coronavirus correction?

You may have got to the point now where you’re like:

“I think that coronavirus is going to push markets lower, so what if I sell now and buy back in later?”

Trying to ‘buy the dip’ is a common thought for new and experienced investors alike. The difference for experienced investors is that, usually, we’ve learned to ignore it.

The reason is timing the market, just like picking stocks, is notoriously difficult, and experienced investors have learned that. They probably have a few scars to remind them too! 😂

In fact, professional investors, whose job it is to analyse and evaluate investments, consistently underperform index funds and ETFs, on average.

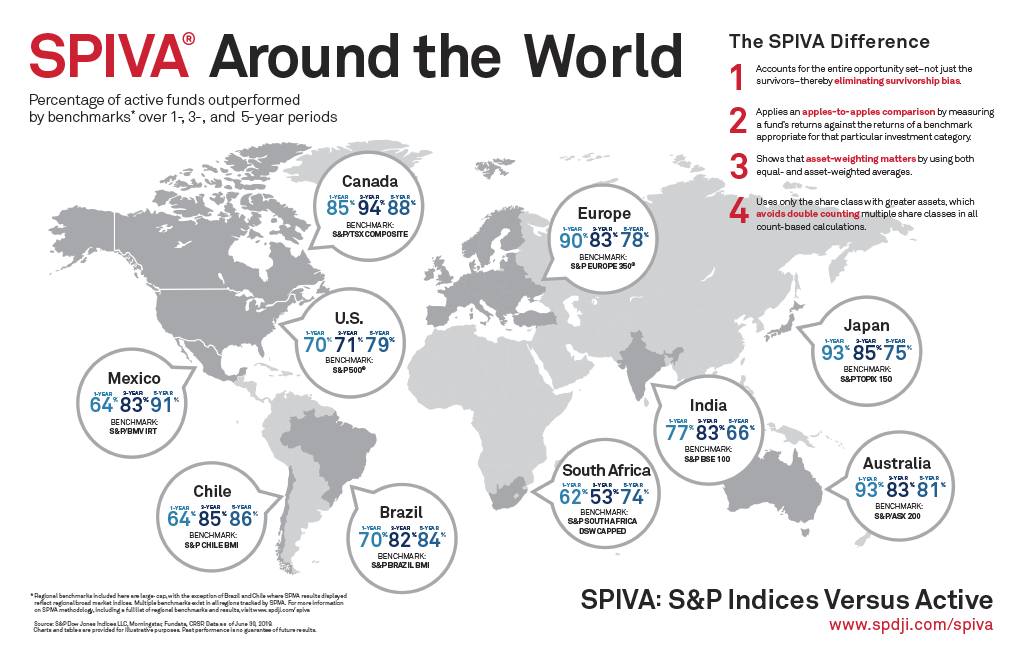

In Australia, 84% of active funds were outperformed by the S&P/ASX 200 Index over the last 15 years. Similar stories hold true across the globe and wherever you’re from, I encourage you to download the latest S&P Indicies versus Active (SPIVA) report to compare the active vs passive data yourself. Remember, timing the market is a first cousin of stock picking - it counts as active too!

The infographic below illustrates the percentage of active funds outperformed by benchmarks over 1-, 3-, and 5-year periods across 10 of the world’s major markets – note that there’s not one period in any market where a majority of active funds outperform…

So, if the vast majority of professionals underperform the index, what hope do retail investors have of picking when the post-coronavirus market has hit rock bottom?

Very little, according to value-investing superstars like Warren Buffet, Peter Lynch, and Benjamin Graham. They've each encouraged retail investors to shun active investment strategies.

In fact, in Berkshire Hathaway’s 2005 Chairman's Letter Warren Buffet went so far as to propose a ‘Fourth Law of Motion’: For investors as a whole, returns decrease as motion increases.

For me, a reformed active investor, in times like these there is a fleeting second where I get tempted to try and time the market too.

Luckily, John Bogle’s Relentless Rules of Humble Arithmetic have become like personal mantras and I soon remember that my previous experiences as an active investor weren’t all that successful.

Instead, back to basics – dollar-cost averaging into my portfolio of ETFs and drinking pina coladas rather than watching the market 🍸

Remember, investing is beautiful when it’s SimpliFI'ed.

The Key Takeaway

We started out on a mission to answer two questions:

- Is coronavirus a short- or long-term crisis?

- Can I reliably time the coronavirus correction?

We discovered that while the answer to 1) is still TBD, it is irrelevant because regardless of whether it’s a short-term or long-term crisis, coronavirus is unlikely to have enough of an economic impact to affect our investing strategies. We are long-term (+10yr!) investors after all 😉

The answer to 2) is more straightforward – a definitive no for >99% of retail investors. Picking the dip is like picking stocks – just not worth it. SimpliFI’ed investing is smart investing.

Key Takeaway: Try to stick to your plan, automate and forget about it. COVID-19 has triggered a crash, but that's no reason to change your strategy.

Happy Investing and Happy FI-ing 🔥

Kurt

***You might be wondering why not compare with Spanish flu or SARS too?

From an infectious-diseases perspective, Spanish flu seems like the best comparison, but since that occurred in the 1920s I’ve found it hard to track down the data. I also think it’s probably not as contextually relevant because the world we live in today is much more globalised – planes had only recently been invented!

SARS is a similar story, China was not nearly as well connected in 2003 during the SARS outbreak. China now has about four times as many train and air passengers as it did during the SARS outbreak (see chart below). SARS was also only contagious when symptomatic and it tended to incapacitate people quickly which meant the spread was low. So while SARS ended up being contained, it’s considered unlikely that COVID-19 will be.

At Pearler, we pride ourselves on the quality of the general financial advice we give. Please note though, that this advice has not been tailored for you. You have unique financial goals, circumstances and needs which may make this advice inappropriate, and it is important that you know whether it applies to you. If you are unsure we urge you to speak to someone you trust who is competent with money and understands your individual needs, whether they be a trusted friend or accredited professional.